Two years ago, GRET began reflections to develop and formulate a “commons-based approach”, aimed at supporting local stakeholders to construct modes of shared governance. We take a look back at a rewarding collective experience.

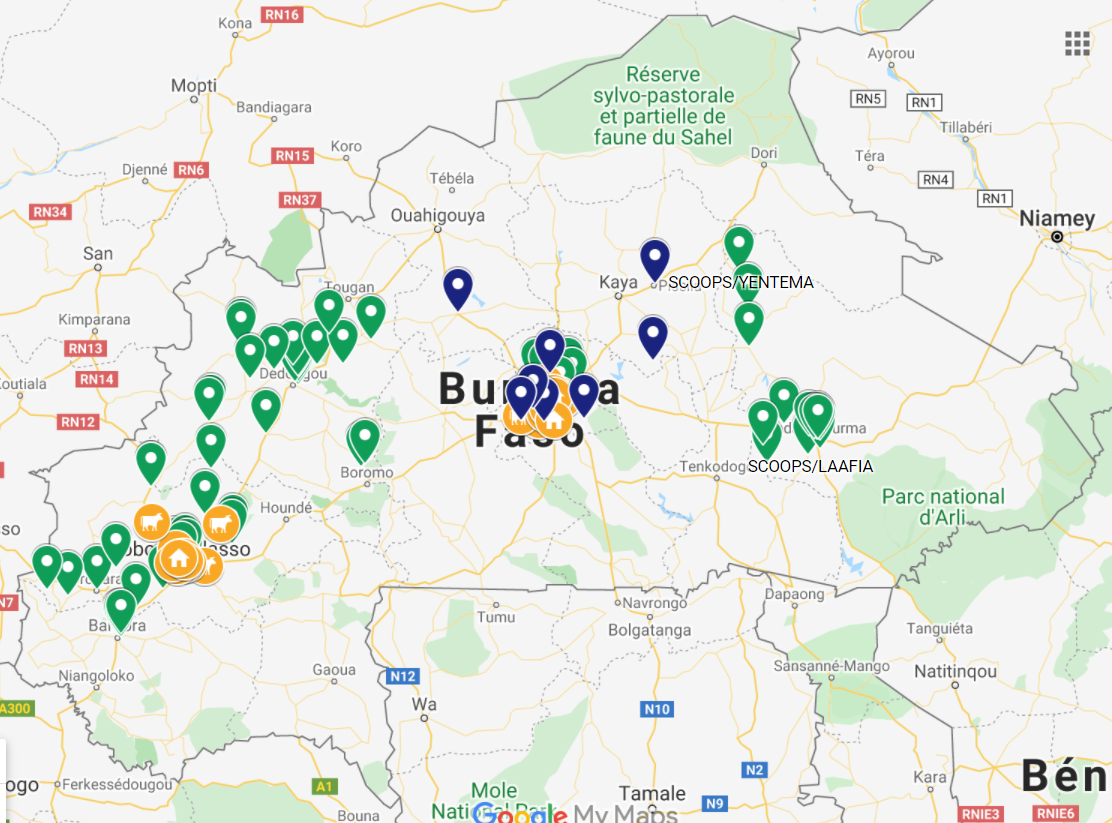

In nine countries in Africa and Asia, and in Madagascar and Haiti, GRET’s teams have been testing since 2019 the adoption of a commons-based approach in field projects. The objective of this testing phase – made possible thanks to a programme agreement signed with Agence française de development that is likely to last nine years – is to highlight more sustainable, equitable and inclusive modes of governance in territories, and to enable feedback on experiences facilitating the development of operational know-how on implementing a common.

Although the implementation of the programme on the commons was impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic, the collective learning dynamic was able to continue. Following on from conceptual work on reflection, definition and formulation of a commons-based approach, GRET’s teams in the various sites supported local stakeholders (users, civil society organisations, public authorities, private stakeholders, etc.) to implement modes of governance that are fairer and more sustainable. This implementation took place in a process of action-research .

From gradual appropriation of the concept of the commons…

Reflections on the commons conducted at GRET were initially based on the work of political scientist Elinor Ostrom, who won the 2009 Nobel Prize for Economics. In an initial definition, a common is made up of resource with shared access, a community of stakeholders with a set of rights (access, use, etc.) and rules established around this resource, via a governance structure.

The programme’s various collective discussions enabled GRET’s teams to continue appropriating the subject with a view to having a dynamic and operational definition of a common, such as a form of social organisation in which a set of stakeholders decide to undertake collective action to build shared governance, capable of defining and implementing a set of sustainable and fair rules for managing rights to access and use an object of common interest (a resource, service or territory).

“This definition, which is more procedural, makes it possible to highlight the importance of collective action and collective learning in the constitution life of a common », says Jean-François Kibler, coordinator of the Commons programme at GRET.

The collective action undertaken by local stakeholders is the starting point for the process of building shared governance and defining rules. It is generally motivated by the necessity to resolve a social dilemma, where tensions are often due to conflicts of interest between the short term and the long term, the individual faced with the collective, around the object of the common. This dilemma is even more present when resources referred to as “common” have shared access (water for example), and it is very difficult to exclude potential users (non-excludability) while using the resource impacts other people’s possibility to also use it (rivalry). The implementation of shared governance and rules on the common resource is intended to solve these potential tensions, to avoid endangering the resource’s sustainability and generating breakdown in dialogue and violence. We talk about shared governance because all stakeholders in the common actively participate in processes for decision-making and management of rules, so that they can periodically evaluate these rules and change them, taking a continuous collective learning approach.

… to formulation of a commons-based approach

The implementation a commons-based approach as part of GRET’s projects is being developed around three areas of focus: a political intention, a conceptual framework and facilitation methods.

The political intention aims to construct fairer, more sustainable modes of shared governance, making sure to strengthen citizen participation in decision-making and management bodies. “Our analyses and intervention strategies mobilise a stringent conceptual framework, in large part inspired by the theoretical framework for the commons, which is complex and constantly evolving, where analyses and reflections generated by projects mutually enrich each other”, explains Marilou Gilbert, the programme facilitator. Support for local initiatives to construct the commons is provided through the development of methods to facilitate dialogue and social construction (dialogue, consultation, forward-planning or negotiation), that involve a broad spectrum of fields of reference, from modelling to popular education. “By creating a context that is favourable to collective action and learning, operationalisation of the approach must enable building of shared governance that ensures citizens’ power to decide and manage… A significant challenge!”, adds Jean-François Kibler.

Varied operational implementations

In the field, one of the first challenges was to identify the purpose of the common, and to characterise its forms and limits. Through a long series of dialogues and exchange of views, GRET’s teams supported the various stakeholders in this process of identification, with a view to arriving at a mode of social organisation representing everyone’s interests.

This identification stage enabled the diversity of the commons to be highlighted. In the city of Luang Prabang in Laos, the common to be constructed focuses on the urban pools network, which will be preserved through the implementation of shared shared governance. In the Haut Katanga province in DRC, an agroforestry perimeter for which GRET supported the creation of a de production cooperative. It is sometimes difficult to discern the limits of a common, as they can be embedded in each other: this question was raised as part of a project in Madagascar where a common can be electricity, an electricity service or a resource generating electricity. In practice, it is clear that it would be pointless to get boxed in with predefined proposals or categories of commons because ultimately they ill be defined and built by populations themselves.

It is important to pay attention to what takes place upstream, at the root of an emerging common. It is about ascertaining stakeholders’ motivations and implementing conditions that are favourable for collective action, mobilisation andand engagement in theand engagement in the construction ofofof shared governance. Comprendre les aspects sur lesquels ces motivations portent s’avère tout aussi essentiel que la définition du common en elle-même. Understanding aspects underpinning these motivations is as essential as the definition of a common itself.

How to analyse stakeholders’ challenges and facilitate social learning?

As a common is a mode of social organisation, it is vital to analyse stakeholder issues and interactions between the various people related to the common, in order to implement frameworks for dialogue and facilitation methods that are favourable to building a sustainable and inclusive mode of governing the resource, service or territory.

At various stages of the projects’ implementation, GRET’s teams develop and test methods of analyses making it possible to understand stakeholders’ issues in terms of interests, influence, power, resources, etc. These can be templates, roadmaps or drawings, and several tools already developed or modelled by researchers have been mobilised within projects, for example the ARDI (Stakeholders-Resources-Dynamiques-Interactions).

In addition, several facilitation methods aimed at facilitating consultation and social dialogue appear very interesting. One of these, role play, was mobilised within several projects in Madagascar and Senegal in particular, proving to be a powerful lever for awareness-raising and dialogue among stakeholders in the common. On the East coast of Madagascar, a role play was tested with support from the Green research unit at Cirad, as part of a project promoting sustainable coastal fishing. As tool to learn about social dialogue, the role play enabled inhabitants to initiate collective formulation of strategic action plans for shared governance of their natural resources, while contributing to creating links between stakeholders. Also in Madagascar, a board game was designed and tested as part of a rural electrification project, to co-construct rules for managing installation électrique.

Which systems to monitor and evaluate the commons?

Reflections also covered methods for monitoring and evaluating the commons being built. Let us recall that in this regard, the process for definition and improvement of the rules relating to a common is continuous. A central aspect is therefore to support stakeholders with the implementation of internal systems to assess the extent to which the rules implemented are respected and the impact of these rules on management and sustainability of the common.

Monitoring and evaluation must also enable assessment of qualitative changes, which can be perceived subjectively, and difficult to perceive via quantitative indicators. The use of videos conveying feedback at regular intervals, inspired by the “Most Significant Change” method, can reveal changes in posture, perception or power on the part of the various participants.

An, with a view to sharing learning

These various reflections and experimentations are part of a transversal action-research approach. A protocol was gradually developed and appropriated by all the teams, defining a methodological framework adapted to suit each context, it invites people to raise questions on existing levers and obstacles, and helps with the definition of hypotheses with a view to formulating strategies for action, and subsequently documenting and evaluating their effects on the emerging commons. This protocol can be used to develop, test and qualitatively evaluate the specific roll-out of the commons-based approach within each of the projects.

Conduct of the Programme itself is underpinned by a collective learning logic, informed in particular by reflection briefs regularly produced by GRET teams working in the field. These briefs focus on the tools, methods and approaches used, and facilitate sharing and capitalisation of experiences. One of the challenges in the coming months will be finalisation of tools to disseminate this learning. A short practical manual for practitioners is currently being drawn up and should provide a range of conceptual materials and methodological tools that can be mobilised so that all involved can define their own intervention strategy.